A Baroque angel I ran across.

My attempt to proffer a smorgasbord of interesting trivia.

One civilized reader is worth a thousand boneheads.

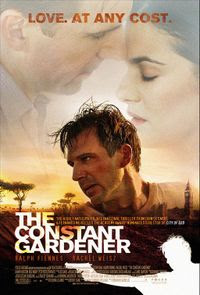

John le Carré is one of the best-selling authors in the English language, and also one of the most poignant. Le Carré studied at the Universities of Berne and Oxford, taught at Eton, and then served on Her Majesty's Secret Service, before he went on to become the unofficial novelist laureate of the world of Western espionage, a world in which he only describes shades of grey, and in which the good and the decent often die young.

John le Carré is one of the best-selling authors in the English language, and also one of the most poignant. Le Carré studied at the Universities of Berne and Oxford, taught at Eton, and then served on Her Majesty's Secret Service, before he went on to become the unofficial novelist laureate of the world of Western espionage, a world in which he only describes shades of grey, and in which the good and the decent often die young."In these dog days when lawyers rule the universe, I have to persist with these disclaimers, which happen to be perfectly true. With one exception, nobody in this story, and no outfit or corporation, thank God, is based on a real person or real outfit in the real world...so with luck, I shall not be spending the rest of my life in the law courts or worse, though nowadays you can never be sure. But I can tell you this. As my journey through the pharmaceutical jungle progressed, I came to realize that, by comparison with reality, my story was as tame as a holiday postcard."

"Johnson and Johnson overstated Risperdal's effectiveness in treating patients with schizophrenia and downplayed the drug's side effects. The suit states that the company also manipulated data collected during development of TMAP, so that Risperdal would appear to be more effective and safer than it actually was. mental health and Medicaid programs were said to have paid "dollars per pill" for Risperdal when it could have paid "pennies per pill" for generic first-generation antipsychotics that were equally effective."

"Expensive new antipsychotic drugs that are among the most widely prescribed pills in medicine are no more effective and no safer than an older, cheaper drug that has been largely discontinued, according to the most comprehensive comparative study ever conducted." In fact, in terms of side-effects, the serious side-effects associated with the older drugs were "less troubling than potentially fatal metabolic problems" associated with some of the newer drugs."

On His Blindness

When I consider how my light is spent,

E're half my days, in this dark world and wide,

And that one Talent which is death to hide,

Lodg'd with me useless, though my Soul more bent

To serve therewith my Maker, and present

My true account, least he returning chide,

Doth God exact day-labour, light deny'd,

I fondly ask; But patience to prevent

That murmur, soon replies, God doth not need

Either man's work or his own gifts, who best

Bear his milde yoak, they serve him best, his State

Is Kingly. Thousands at his bidding speed

And post o're Land and Ocean without rest:

They also serve who only stand and waite.

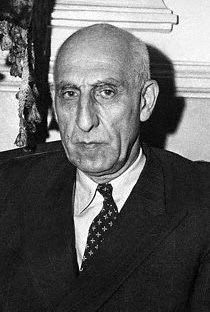

Not long ago, while the drums of war with Iran were beaten more loudly than they are today, I took the time to read Musaddiq and the Struggle For Power in Iran by Homa Katouzian, a fellow at Saint Anthony College, Oxford.

This is a book that requires thoughtful reading to really be enjoyed. At heart, it is an elegy for the

Mohammed Mossadeq was born in 1882, as the son of an offic ial in the Iranian Finance Ministry, and a princess of the Qajar Dynasty, the dynasty that was supplanted by the Pahlavis. He began undergraduate work at the Sci-Po in

ial in the Iranian Finance Ministry, and a princess of the Qajar Dynasty, the dynasty that was supplanted by the Pahlavis. He began undergraduate work at the Sci-Po in

Upon returning to

The coup restored the reluctant Shah to his throne; Mossadeq first spent some years in solitary confinement, and then even more years under house arrest. Nor were these the only tragedies he endured; a child of his developed severe life-long psychiatric problems, which Mossadeq described as "the cruelest fate that can befall a parent." American oil companies got part of what had previously been an exclusively British pie; the hapless AIOC was left with less than the Iranians had at one point offered it. But the real losers were the Iranians; instead of living in a fledgling democracy that aspired to imitate the West, without forsaking its traditions, they found themselves living in an increasingly corrupt regime maintained in power by the Western democracies, with a secret police schooled in the fine art of torture by Israeli advisors.

The coup restored the reluctant Shah to his throne; Mossadeq first spent some years in solitary confinement, and then even more years under house arrest. Nor were these the only tragedies he endured; a child of his developed severe life-long psychiatric problems, which Mossadeq described as "the cruelest fate that can befall a parent." American oil companies got part of what had previously been an exclusively British pie; the hapless AIOC was left with less than the Iranians had at one point offered it. But the real losers were the Iranians; instead of living in a fledgling democracy that aspired to imitate the West, without forsaking its traditions, they found themselves living in an increasingly corrupt regime maintained in power by the Western democracies, with a secret police schooled in the fine art of torture by Israeli advisors.I think a leader who would have been willing to make unpleasant, and perhaps even humiliating compromises, dictated by the political realities of the day, in order to negotiate a better deal on a better day, would have left Iran in a much better position that a leader who demanded everything, and got nothing.

Like every other country, Iran is not perfect; this book describes ho w it went from being a normal country in its day to a (reluctant) dictatorship, and then convulsed into the Islamic Republic of Iran. There is a parallel for this in English history; without Charles I, who asserted his divine rights as a king, and buttressed his claims in his infamous Star Chamber, Oliver Cromwell would never have come to be the Lord Protector of England, Commander of the New Model Army, praised by John Milton, and, to this day, an epithet among the Irish. Were it not for the Shah and his fearsome secret police, the Ayatollah Khomeini and the Iranian Revolutionary Guards would never have attained the prominence they did. Regimes that truck heavily in religious zealotry are neither new nor exclusive to the Middle East, and not infrequently result as a reaction to iniquitous governments. Generally if left to their own devices, such regimes, like teenagers caught in the tempests of puberty, become less strident with time. Under Oliver Cromwell, all theaters were closed as immoral and decadent; yet England and English literature recovered.

w it went from being a normal country in its day to a (reluctant) dictatorship, and then convulsed into the Islamic Republic of Iran. There is a parallel for this in English history; without Charles I, who asserted his divine rights as a king, and buttressed his claims in his infamous Star Chamber, Oliver Cromwell would never have come to be the Lord Protector of England, Commander of the New Model Army, praised by John Milton, and, to this day, an epithet among the Irish. Were it not for the Shah and his fearsome secret police, the Ayatollah Khomeini and the Iranian Revolutionary Guards would never have attained the prominence they did. Regimes that truck heavily in religious zealotry are neither new nor exclusive to the Middle East, and not infrequently result as a reaction to iniquitous governments. Generally if left to their own devices, such regimes, like teenagers caught in the tempests of puberty, become less strident with time. Under Oliver Cromwell, all theaters were closed as immoral and decadent; yet England and English literature recovered.

If you’re interested by the history of modern Iran, and are skeptical of the Manichean understanding of Iran (ironic isn't it that Manichaeism is a philosophy of Iranian origin?) which some right-wing nuts are promoting, or have lingering doubts whether a book that raves about reading a book describing the doings of a sexual predator (Reading Lolita in Tehran) is the most informative and unbiased introduction to contemporary Iran, you'll enjoy Katouzian's biography. I suspect it was written for Iranians and academics; as such, it's a good introduction to the history of Iran by an Iranian historian. Another advantage of the book is that rather than being focused on a single episode or a single aspect of Iran's history in the 20th century, it is a sort of Bildungsroman of a man and country with, alas, a tragic ending.

And Katouzian's book.![]()

"The commerce of Lucerne consists mainly in gimcrackery of the souvenir sort; the shops are packed with Alpine crystals, photographs of scenery, and wooden and ivory carvings. I will not conceal the fact that miniature figures of the Lion of Lucerne are to be had in them. Millions of them. But they are libels upon him, every one of them. There is a subtle something about the majestic pathos of the original which the copyist cannot get. Even the sun fails to get it; both the photographer and the carver give you a dying lion, and that is all. The shape is right, the attitude is right, the proportions are right, but that indescribable something which makes the Lion of Lucerne the most mournful and moving piece of stone in the world, is wanting.The Lion lies in his lair in the perpendicular face of a low cliff--for he is carved from the living rock of the cliff. His size is colossal, his attitude is noble. How head is bowed, the broken spear is sticking in his shoulder, his protecting paw rests upon the lilies of France. Vines hang down the cliff and wave in the wind, and a clear stream trickles from above and empties into a pond at the base, and in the smooth surface of the pond the lion is mirrored, among the water-lilies.

Around about are green trees and grass. The place is a sheltered, reposeful woodland nook, remote from noise and stir and confusion--and all this is fitting, for lions do die in such places, and not on granite pedestals in public squares fenced with fancy iron railings. The Lion of Lucerne would be impressive anywhere, but nowhere so impressive as where he is.

Martyrdom is the luckiest fate that can befall some people. Louis XVI did not die in his bed, consequently history is very gentle with him; she is charitable toward his failings, and she finds in him high virtues which are not usually considered to be virtues when they are lodged in kings. She makes him out to be a person with a meek and modest spirit, the heart of a female saint, and a wrong head. None of these qualities are kingly but the last. Taken together they make a character which would have fared harshly at the hands of history if its owner had had the ill luck to miss martyrdom. With the best intentions to do the right thing, he always managed to do the wrong one. Moreover, nothing could get the female saint out of him. He knew, well enough, that in national emergencies he must not consider how he ought to act, as a man, but how he ought to act as a king; so he honestly tried to sink the man and be the king--but it was a failure, he only succeeded in being the female saint. He was not instant in season, but out of season. He could not be persuaded to do a thing while it could do any good--he was iron, he was adamant in his stubbornness then--but as soon as the thing had reached a point where it would be positively harmful to do it, do it he would, and nothing could stop him. He did not do it because it would be harmful, but because he hoped it was not yet too late to achieve by it the good which it would have done if applied earlier. His comprehension was always a train or two behindhand. If a national toe required amputating, he could not see that it needed anything more than poulticing; when others saw that the mortification had reached the knee, he first perceived that the toe needed cutting off--so he cut it off; and he severed the leg at the knee when others saw that the disease had reached the thigh. He was good, and honest, and well meaning, in the matter of chasing national diseases, but he never could overtake one. As a private man, he would have been lovable; but viewed as a king, he was strictly contemptible.

His was a most unroyal career, but the most pitiable spectacle in it was his sentimental treachery to his Swiss guard on that memorable 10th of August, when he allowed those heroes to be massacred in his cause, and forbade them to shed the "sacred French blood" purporting to be flowing in the veins of the red-capped mob of miscreants that was raging around the palace. He meant to be kingly, but he was only the female saint once more. Some of his biographers think that upon this occasion the spirit of Saint Louis had descended upon him. It must have found pretty cramped quarters. If Napoleon the First had stood in the shoes of Louis XVI that day, instead of being merely a casual and unknown looker-on, there would be no Lion of Lucerne, now, but there would be a well-stocked Communist graveyard in Paris which would answer just as well to remember the 10th of August by."

Little needs to be added to Twain's synopsis of the Lion Monument other than its history. When the survivors of the massacres returned to Switzerland, the eve of the French revolution was nigh; it was not until after the madness and bloodshed of the French Revolution and Napoleon ended at Waterloo that erecting a monument to their fallen comrades in arms became feasible. Led by Karl Pfyffer von Altishofen, (1771-1840), one of their lieutenants, they began collecting money for the monument in 1818; the monument, whose construction was supported by, among others, the Czar of Russia, and the Kings of Prussia and France, was unveiled on August 10, 1821, the 29th anniversary of the massacre.

A small hint for thoughtful visitors to the monument: Don't forget to also get a look at the memorial chapel that is also part of the Lion Monument, and which is not shown to the flocks of tourists, with its inscriptions of "Invictis Pax," that is "Peace to the Undefeated" and "Per vitam fortes, sub iniqua morte fideles," "In life brave, faithful in an unjust death." If you can muster expected in a church, it is worth seeing.