John le Carré is one of the best-selling authors in the English language, and also one of the most poignant. Le Carré studied at the Universities of Berne and Oxford, taught at Eton, and then served on Her Majesty's Secret Service, before he went on to become the unofficial novelist laureate of the world of Western espionage, a world in which he only describes shades of grey, and in which the good and the decent often die young.

John le Carré is one of the best-selling authors in the English language, and also one of the most poignant. Le Carré studied at the Universities of Berne and Oxford, taught at Eton, and then served on Her Majesty's Secret Service, before he went on to become the unofficial novelist laureate of the world of Western espionage, a world in which he only describes shades of grey, and in which the good and the decent often die young.His 2001 novel, The Constant Gardener begins with the troubled marriage of a British diplomat posted in Africa, progresses to his wife's murder in the African bush; as the plot further unfolds, Le Carré initiates us into an almost Ludlumlesque world of faked clinical trials and of pharmaceutical companies that will stop at nothing, and certainly not dead diplomats, in their quest for lucre. Unlike other novels by Le Carré, such as The Spy Who Came in From the Cold, which is good for unforeseen plot twists right up to the last page, towards its end, The Constant Gardener's plot is close to formulaic. This may not be a artistic flaw, but rather a reason to ponder why Le Carré forces his readers to plod through a good hundred pages devoted primarily to the ends and means of a hypothetical pharmaceutical company.

begins with the troubled marriage of a British diplomat posted in Africa, progresses to his wife's murder in the African bush; as the plot further unfolds, Le Carré initiates us into an almost Ludlumlesque world of faked clinical trials and of pharmaceutical companies that will stop at nothing, and certainly not dead diplomats, in their quest for lucre. Unlike other novels by Le Carré, such as The Spy Who Came in From the Cold, which is good for unforeseen plot twists right up to the last page, towards its end, The Constant Gardener's plot is close to formulaic. This may not be a artistic flaw, but rather a reason to ponder why Le Carré forces his readers to plod through a good hundred pages devoted primarily to the ends and means of a hypothetical pharmaceutical company.

Le Carré has always had an ear to the ground, and not only described human nature but also addressed the problems of the day in his books. Yet in none of his other books that I have read, does the focus of the book drift from its ostensible agonists to their antagonists to such a degree. In Le Carré's other books, bad things happen, people are cruel, but such is life. The explanation for this departure from precedent is, I believe, revealed at the end of the book, when he writes:

The Science is Getting to be Rather DilutedLe Carré has always had an ear to the ground, and not only described human nature but also addressed the problems of the day in his books. Yet in none of his other books that I have read, does the focus of the book drift from its ostensible agonists to their antagonists to such a degree. In Le Carré's other books, bad things happen, people are cruel, but such is life. The explanation for this departure from precedent is, I believe, revealed at the end of the book, when he writes:

"In these dog days when lawyers rule the universe, I have to persist with these disclaimers, which happen to be perfectly true. With one exception, nobody in this story, and no outfit or corporation, thank God, is based on a real person or real outfit in the real world...so with luck, I shall not be spending the rest of my life in the law courts or worse, though nowadays you can never be sure. But I can tell you this. As my journey through the pharmaceutical jungle progressed, I came to realize that, by comparison with reality, my story was as tame as a holiday postcard."

One of Ronald Reagan's more amusing stories about life in the old Soviet Union concerned an oblast (district) in which the party official responsible for milk production sent out a telegram to the 49 Kolkhozes (collective farms) ordering them to increase milk output by 10%. A week later, 49 telegrams came back reporting that milk production at all 49 Kolkhozes had indeed increased by 10%. Consequently, out went the next telegram; a week later 31 had been able to raise their milk production by another 10%. A week and another telegram later, 17 had upped their milk production by a cumulative 30%. The next week, 5 Kolkhozes reported that they had been able to increase their milk output by yet another 10%, but when yet another telegram demanding yet another 10% increase went out, only one Kolkhoz replied, plaintively: "Don't you think our milk is getting to be rather diluted?"

Since 2001, scandal after scandal has broken, which serve to confirm the validity of Le Carré's cri de coeur against the pharmaceutical industry. Among them are:

- reports that children died when Pfizer tested a new antibiotic against meningitis in Nigeria without obtaining the informed consent of the patients or the approval of the ethics board at the hospital at which the tests were conducted. A letter from an ethics board that appears to approve these tests is somewhat dubious; according to a doctor at the hospital, at the time the letter was written, the hospital in question allegedly didn't even have an ethics board.

- Nor is this all. Because the drug used as a comparison to Pfizer's new drug is generally given as an IV, but this was not feasible under the conditions of the clinical trials, the comparison drug was given at a dose "much smaller than originally planned," to minimize the pain suffered by the patients during the injections. Of course if the dose of the comparison drug was inadequate, which Pfizer denies, then its investigative drug stood to appear to be so much better than the benchmark to which it was compared. Whatever the facts may be, the manufacturer of the comparison drug maintains that "A high dose is essential." Not that some didn't allegedly voice their concerns at the time of the trials. According to the British Medical Journal, "The suit notes that Dr Juan Walterspeil, an specialist in infectious diseases who was assigned to the test, repeatedly warned Pfizer that it was violating international laws, federal regulations, and medical ethics. Dr Walterspeil was subsequently fired.

- the Vioxx debacle, where Merck was forced to withdraw a drug after it was found to be four times likelier to induce a heart attack than a comparison drug. The most chilling aspect of the scandal is that Merck appears to have known of this problem, to have fought efforts to get to the bottom of the problem tooth and nail, and even to have designed clinical trials so as to minimize and misrepresent the number of heart attacks that Vioxx was going to cause.

- the Texas Medication Algorithm Project scandal. Though is not yet been tried, there's a whistle-blower lawsuit in which the Attorney General of Texas alleges that:

"Johnson and Johnson overstated Risperdal's effectiveness in treating patients with schizophrenia and downplayed the drug's side effects. The suit states that the company also manipulated data collected during development of TMAP, so that Risperdal would appear to be more effective and safer than it actually was. mental health and Medicaid programs were said to have paid "dollars per pill" for Risperdal when it could have paid "pennies per pill" for generic first-generation antipsychotics that were equally effective."

- What happened specifically? A recent large scale comparison of newer medications, which can cost $5 or more per dose, with older medications, that generally cost less than a quarter found, according to the Washington Post (New Antipsychotic Drugs Criticized, Federal Study Finds No Benefit Over Older, Cheaper Drug, September 20, 2005 page A1):

"Expensive new antipsychotic drugs that are among the most widely prescribed pills in medicine are no more effective and no safer than an older, cheaper drug that has been largely discontinued, according to the most comprehensive comparative study ever conducted." In fact, in terms of side-effects, the serious side-effects associated with the older drugs were "less troubling than potentially fatal metabolic problems" associated with some of the newer drugs."

- Evidence and common sense suggest that the manufacturers of the newish drugs would have had some idea that these sorts of results might be reported. This could explain why when they funded trials to determine which drugs worked best, their new drugs were not directly compared to the then prevalent treatments; instead the scientists reportedly compared a regimen of the older drugs to a regimen of the new drugs and group education, consumer to consumer discussion groups, individual patient education from the physician, referrals to therapy groups and more. Even at the time, there were rumors that science was not the only consideration in these studies. I cannot predict the verdict, but, in my opinion, it stinks to high heaven.

- the credible, in my opinion convincing, allegations that America's bumper crop of autistic children has been caused by the vaccines that parents have been expected to pay for and let doctors inject into their children.

When you have 4 such scandals break, and the allegations involve forged documents, the firing of a doctor who wanted to play by the rules, the rigging of clinical trials, and more, you have a serious problem. And when such scandals surface with a worrying frequency, it stands to reason that they are but the tip of the iceberg; a truer number might be 40, or 400, or more. We can only guess at which of our own health care decisions are made on the basis of "highly diluted" data.

The Road to Serfdom

If you take the time to think about all this, the surprising thing is not that these scandals have occurred; what would be truly surprising is if they didn't occur. What you have here, is that many of the weaknesses of our capitalist system overlap, with catastrophic results.

1) For starters you have pharmaceutical companies, whose primary legal responsibility is to maximize profits, and who make significant financial contributions into the political process, obviously to politicians agreeable to their interests. To suggest that big pharma gets nothing in return for its donations is to imply that its executives are utter morons.

2) Pharmaceutical companies also plow a lot of money into advertising, which may account for why large parts of the media are generally reticent about running articles that are scathingly critical of the products for which, and companies to which, they sell advertising space.

3) Another huge problem is serfdom in academia. In the United States, the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution bans outright slavery. Unfortunately, it has nothing to say about people who have spent the best years of their life working to obtain an MD or PhD, and believe that if they wish to reap the returns of those years spent studying, they had better be a team player. At least one scientist indisposed to be a "team player" seems to find life easer outside of the United States.

If you at this point still have any illusions about just how deeply deficient medicine in America is, allow me to recommend that you read "On the Take: How Medicine's Complicity with Big Business Can Endanger Your Health ," by Jerome Kassirer, MD, a former editor-in-chief of the New England Journal of Medicine. Kassirer tells of his having received a "no strings attached" contract to give talks to his fellow physicians. But when he disdained to don rose-colored glasses, and definitely didn't go out of his way to contort his talks to the benefit of his sponsor's products, he found that his contract was not renewed. More pliant doctors were retained. This, he writes, is the rule, not the exception. Kassirer cuts through the euphemisms to describe how and why medicine in his experience, has become a parody of what it ought be, something more suited to the recesses of Franz Kafka's fertile imagination. As Kassirer summarizes his experiences: "Some physicians become known as whores."

," by Jerome Kassirer, MD, a former editor-in-chief of the New England Journal of Medicine. Kassirer tells of his having received a "no strings attached" contract to give talks to his fellow physicians. But when he disdained to don rose-colored glasses, and definitely didn't go out of his way to contort his talks to the benefit of his sponsor's products, he found that his contract was not renewed. More pliant doctors were retained. This, he writes, is the rule, not the exception. Kassirer cuts through the euphemisms to describe how and why medicine in his experience, has become a parody of what it ought be, something more suited to the recesses of Franz Kafka's fertile imagination. As Kassirer summarizes his experiences: "Some physicians become known as whores."

1) For starters you have pharmaceutical companies, whose primary legal responsibility is to maximize profits, and who make significant financial contributions into the political process, obviously to politicians agreeable to their interests. To suggest that big pharma gets nothing in return for its donations is to imply that its executives are utter morons.

2) Pharmaceutical companies also plow a lot of money into advertising, which may account for why large parts of the media are generally reticent about running articles that are scathingly critical of the products for which, and companies to which, they sell advertising space.

3) Another huge problem is serfdom in academia. In the United States, the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution bans outright slavery. Unfortunately, it has nothing to say about people who have spent the best years of their life working to obtain an MD or PhD, and believe that if they wish to reap the returns of those years spent studying, they had better be a team player. At least one scientist indisposed to be a "team player" seems to find life easer outside of the United States.

If you at this point still have any illusions about just how deeply deficient medicine in America is, allow me to recommend that you read "On the Take: How Medicine's Complicity with Big Business Can Endanger Your Health

4) What further complicates the situation is the complexity of the science involved. The average lay person has next to no chance of figuring out what is true and what is scientific fiction. And so the best he or she can do is to hope that whatever their doctors decide is wise, and hope, and maybe pray, for the best.

In other words, politicians, torn between easy contributions and complicated science, often fail their constituents. The media, which has to choose between easy advertising revenue and painstaking investigative reporting, does its duty to its stockholders. Physicians and scientists, torn between their conscience and the demands of the job, make their compromises. With the deck stacked so badly, the average lay person has little, if any chance, of getting to the bottom of anything.

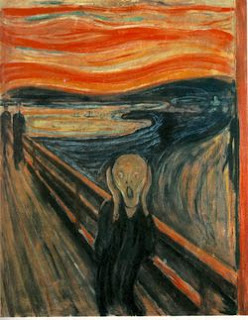

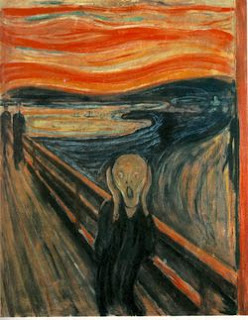

Once upon a time, I couldn't fathom how disasters such as Chairman Mao's Cultural Revolution, the Ukrainian Famine of 1932-1933, or the Holocaust could happen. Today the answer seems all too clear to me: spineless (and worse) politicians, a supine (if not craven) press, and professionals and officials keen to be team players are all it really takes to make a huge mess of things. I am convinced that in a hundred or so years, people looking back on the 1990s and today will remark that some of what happened in our day, such as advances in semi-conductors, the internet, genetic research, and more were really impressive. But when it comes to today's medicine, I am convinced that they will only laugh.

When I was a little younger, and a little more foolish, I occasionally felt a little smug when I saw pictures of life in Cuba, where the vast majority of the cars on the road date back to the 1950s, to the time before the embargo of Fidel Castro's Cuba. Little did I know that some of the medical treatments that I, and millions of others, had received, or would receive, were based on technologies that dated back to the 1950s, and even the 1850s, and that scientists who had tried to update our understanding of these treatments had seen their efforts be discredited by research that stinks to high heaven, and, in one memorable case, was even threatened with deportation if he didn't abandon his academic pursuits. I would much rather have to drive a car that dates back to the 1950s than have to see a doctor who, without realizing it, is still caught in the 1950s in some of his opinions. The sad fact is that the joke is on all of us.

When I was a little younger, and a little more foolish, I occasionally felt a little smug when I saw pictures of life in Cuba, where the vast majority of the cars on the road date back to the 1950s, to the time before the embargo of Fidel Castro's Cuba. Little did I know that some of the medical treatments that I, and millions of others, had received, or would receive, were based on technologies that dated back to the 1950s, and even the 1850s, and that scientists who had tried to update our understanding of these treatments had seen their efforts be discredited by research that stinks to high heaven, and, in one memorable case, was even threatened with deportation if he didn't abandon his academic pursuits. I would much rather have to drive a car that dates back to the 1950s than have to see a doctor who, without realizing it, is still caught in the 1950s in some of his opinions. The sad fact is that the joke is on all of us.

Why I am Cautiously Hopeful

The good news is the bad news: if things don't get better, they are going to get a lot worse. Like being pregnant, for a country, being corrupt is a binary option: no country can be "just a little corrupt." Either it has sensible laws and meaningful institutions to stamp out corruption and enforce its laws, or it doesn't. If the latter is true, it is only a matter of time until corruption metastasizes throughout the entire body politic. Look no further than Robert Mugabe's Zimbabwe, once a prosperous exporter of agricultural commodities. Now that a clique of barbarians has seized power, the country has reached the point where it can no longer feed its people. It is the very starkness of the possible alternatives facing us that makes me optimistic.

Encouragingly there already are signs that these much needed reforms are beginning. Whistle-blowers have found the support they need to go public; the TMAP scandal was uncovered by one of them. The litigation over thimerosal has begun. And there are some excellent blogs that provide the critical coverage that the lame-stream media so badly lacks. Among the best of them are the Alliance for Human Research Protection, and Scientific Misconduct by a scientist who put science first. I highly recommend them.Ten years ago, to publicly talk about such widespread problems in medicine was often to court concerns about your good judgment. Today, to post about the these widespread problems, and link to evidence for your conclusions, is not necessarily terribly common, but within the mainstream. I am convinced that in ten years' time, to not believe that medicine, as we knew it in 2007, was a complete mess, will have become a way of raising worries about your good judgment. We shall see.

Links:

The Alliance for Human Research Protection blog.

The Scientific Misconduct Blog

Books:

John Le Carré: The Constant Gardener

Jerome Kassirer, MD: On the Take: How Medicine's Complicity with Big Business Can Endanger Your Health

The Movie:

The Constant Gardener with Ralph Fiennes and Rachel Weisz (Widescreen Edition)